Kenya is a land of contrasts. We are blessed with a variety of cultures, creeds, traditions, and geographical features. From one region to the other, we all do our things in our unique way. That’s the beauty of our country.

And that beauty and uniqueness is seen in how each region is using EdTech apps and gadgets. For instance, though they are slaying the same dragon—foundational literacy and numeracy—the approaches of Samuel Okoth and Abdullahi Maalim are different.

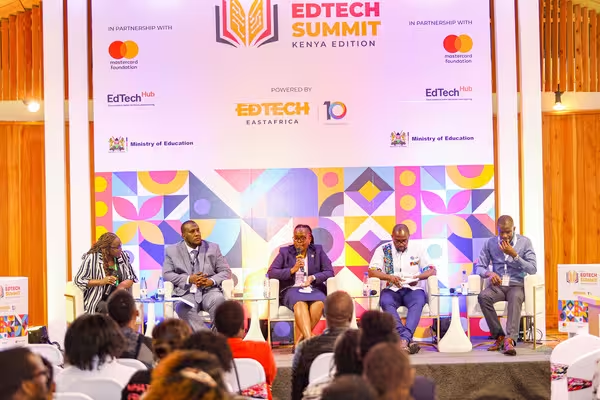

Sam is with the Africa Math Initiative and is based in Western Kenya. Abdullahi is the Education and Governance Sector Lead at the Frontier Counties Development Council (FCDC). Both panelists face different challenges from those affecting Elizabeth Ndung’u and Paul Akwabi. Elizabeth is the Director of Digital Economy and Startups at Nairobi County. Paul is the Executive Director of Tech Kidz Africa, based in Mombasa.

Four different regions: Western, Northeastern (Frontier counties), Nairobi, and Mombasa, and an opportunity to learn from each other, among other things, how to upscale EdTech solutions.

Correcting historical learning injustices

The Frontier Counties Development Council (FCDC) was established to address historical challenges rooted in the 1964 Kenyan Sessional Paper, which prioritized high-potential areas. This led to remoteness, isolation, insecurity, droughts, and more recently, terror-related issues, limiting the region’s educational progress in areas like access, inclusivity, quality, infrastructure, digital content, and teacher availability.

All these have denied the council and the region the opportunity to appreciate the key performance indicators in education, including issues on access and inclusivity, quality education, infrastructure, digital content, and proper delivery of education as a result of shortages of teachers.

“And it’s because of that we felt, now that we are not involved physically, we should not be left behind digitally,” Abdullahi explained. And we want to correct all the gaps that came as a result of the many years of low involvement in these areas with a lot of digital integration.”

“We’re happy that there are many organizations that came into play, knowing very well the SDG Goal of leaving no one behind. So under that rider, we were able to start this cooperative and cooperate with many organizations that are doing a lot of work, including the Ministry of Education, under the very ambitious Digital Literacy Project of 2013, which had its issues, but it has provided the latitude for organizations to come on board.”

The regional summit that was held in the north unpacked many issues. Not only that. It also created opportunities. During that forum, FCDC launched two very critical digital programs. The E-book, ECD Digital Literacy, which is serving 150,000 learners in the Northeastern region. Raspberry Pi Foundation, a charity organization based in the UK, also came on board. It is supporting about 14,000 learners in grades four to eight, in eight of the 10 FCDC counties.

Demystifying math

“Anyone from the western part of Kenya will tell you that we have very dull classroom environments and very dull learning environments,” Samuel noted. “You will also agree with me if you are from the western part of Kenya that our anxiety towards math learning affects our children and in turn, affects how math is perceived.”

Samuel and his team are trying to demystify math. They believe that maths is not a hard subject that can only be done by the smartest of the bunch. They believe that math learning should start early – at ages two or three – even before a child sets foot inside a classroom.

Samuel says that it doesn’t take a trained teacher to start teaching one’s child math. Your house help will do. With the help of an app, Early Family Math, your child can be doing and loving math at home. Your child can learn math through stories and activities that are fun and engaging. Plus, they can facilitate playful interaction between the parents and the child.

Meaningful relationships can be created out of this. The parents can foster their child’s education. And children can also be supported when they take what they learn in the classroom back at home. Starting early will give your child a head start.

Socio-economic activities and beliefs

While Abdullahi is working to correct historical learning injustices and Samuel is crunching numbers to demystify math, Paul is hard at work—down at the coast—trying to deal a death blow to socio-economic activities and beliefs that have hampered education in Mombasa and its environs.

“It’s ironic, but there are so many unique things in Mombasa that are not even in Nairobi,” Paul said. “At some point, they will die. But when they go to Nairobi and other parts of the country, they will thrive. Mombasa was, in 2019, the first county to start robotics and coding from early childhood. This was a life-changing project. But, unfortunately, it died.”

“The biggest things that affect us are socio-economic activities and beliefs. We also have a high rate of school dropouts. And we are not talking about Mombasa as a city, but also places like Kilifi and Kwale.”

Paul has witnessed it all. He has witnessed how culture affects entire populations and causes retrogression. Besides, the number of locals who are teachers is few and in-between. This means that the Coast region has to get teachers from other communities.

“That becomes the first barrier within the community. They don’t have role models. They don’t have people they know within their community that they can relate to who can be a teacher.”

There are also infrastructural challenges and well as limited access to STEM. But even with all this, there are many organizations that have penetrated the market.

The Coast region is among the best places to pilot any edtech solution,” Paul opined. “And that’s because of the already pre-existing resistance. Because of the resistance that is there already, they start rejecting it from the get-go because it is coming from the West. Some of them still hold on to the belief that the West has ill intentions.”

Paul and Co. realised that, as an organization, they could bring in other partners, both global and local, and spur a synergistic working relationship between them and the county government. Speaking of which, they currently have a project that is working just in Mombasa County in partnership with Raspberry Pi Foundation for teachers to be able to integrate technology into their classrooms.

“We are talking about an English teacher being able to teach coding or storytelling just using coding. We are talking about a mathematics teacher being able to teach technology, infusing technology in learning as compared to when a teacher is projecting or using a projector and is telling you that he is using technology to teach math.”

Understanding how government works

Being the capital city, Nairobi is not just the melting pot of the East African region, but it is a crucible of sorts. It’s the place where different people from diverse backgrounds converge for work, business, learning, leisure, and other activities. As such, for instance, there are disparities in wealth as—in some cases—persons living in informal settlements right next to plush neighborhoods.

“People assume that, in Nairobi, schools are overstaffed,” Elizabeth said. “But nothing could be further from the truth. Looking at the ratio of the resources, both human and physical resources, we still find that there is a great challenge.”

Nairobi has about 230 early childhood public schools. When you divide the number of learners with the meager government resources, you will find that the resources are not adequate.

Nairobi has the highest number of private schools. Yet, not all Nairobi children have access to education because the numbers are incredibly high. There are different types of schools in Kenya. The Basic Education Act (2013) defines two categories, namely public and private schools, while the Alternative Providers of Basic Education and Training (APBET) Guidelines provide another by defining APBET schools. The APBET Policy and Guidelines (2016) are silent on the nature of ownership required for APBET schools.

Nairobi has approximately 1,300 under-childhood teachers, yet they are not enough to serve the number of learners who attend schools.

“When it comes to partnership, something that many people don’t have an understanding of is how the government works,” Elizabeth pointed out. “The government works with a document, a five-year document called County Integrated Development Plan. And it is on the county website.”

“When we look at it, we’ll guide you with the programs the county has planned for the next five years and then you can see how we plan it. We also, from there, have an annual development plan. And the county government year runs from 1st July to June 31st the following year.”

Collective action

The organizations that are on the ground are doing a lot of co-creation and co-design. This means that the solutions that they come up with, even if they are simple solutions, are the right solutions for that community. Why? Because the community has been involved in creating a solution for the problem.

EdTech East Africa has had collective action work ongoing for the past year. Looking at the challenges facing each region, and looking at what communities are doing under different pillars – foundational learning, skills for the future, equity and inclusion, supporting the capacity of leaders of learning, and then looking at what our policies say and the evidence – what the communities are doing is commendable.

There are a lot of good things happening on the ground. Partners are collaborating on the ground and implementing different programs. That is the way to go.

Conclusion

We may come from different regions and we are faced with different challenges. But just as education is the great equalizer, its sidekick is technology. Technology is an enabler but still, it can be integrated in class.

This is something that is happening in Mombasa County. They have other projects for teachers learning AI. They also have IREX, which has programs in different schools within the coastal regions, where they teach coding without using any computer.

The same is happening in Western Kenya with apps like Early Family Math and other edtech solutions. Then there is FCDC and its partners. Each region is doing what works for them. But, in the grand scheme of things, it all adds up and the whole nation benefits.

As the Swahili adage goes, “Haba na haba hujaza kibaba.” Little by little fills the measure. A little from all the stakeholders, a little from all the regions, and, in due time, our nation will be miles ahead.